After deciding to go all-electric for my BIAB brewing setup, I considered how to control the heatstick. I wanted something more than an ON/OFF switch. or simply plugging/unplugging the brewstick from the outlet.

Originally, I did not consider a PID as adding a thermocouple into the mix was over-complicating things in my view. I settled on a design that was detailed in the Homebrewtalk forum and used a small circuit card to control a solid state relay which switched power to the heatstick.

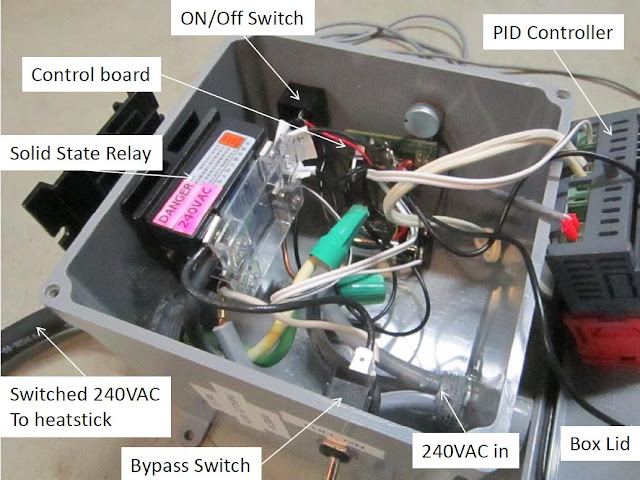

The picture below shows the semi-rat's nest inside my box. One day I hope to clean it up a bit. My apologies for not having it all prettied up like many of the other projects I have seen detailed.

The first version of this box used the Control Board to turn on the relay every so often based on the setting of the potentiometer (round silver component on far side of box). By turning the knob on the outside of the box (connected to the potentiometer), I could control whether the heatstick was on for 1 second every 12 seconds, all the way up to 11.5 seconds of every 12 second interval. The relay switched one of the 2 phases of 120VAC to the heatstick, effectively turning it on and off.

This worked OK during mashing (although still not ideal), but to get my pot up to boil, I needed the heatstick on all the time.

To accomplish this I added the Bypass Switch (shown above) that bypasses the relay, and (when turned ON) keeps the heatstick on continuously. Once I got to a boil, I turned this off, and went back to the timer (technically a variable duty-cycle) approach circuit to control the heatstick.

Since the heatstick is so powerful (5500W), I could not keep a constant boil using the timer circuit. The instant the timer switched off the heatstick the boil would stop. So I decided to buy one of the PIDs so often seen in homebrew projects to see if that would improve the boil as well as the mash temperature control. Mine was around $20 on ebay and displays temperature in degrees C.

With the PID installed, I was able to control temperature quite nicely by dropping the thermocouple into my pot and setting the digital controller (PID) to the desired temperature.

I no longer need the Controller Board in the box, but have left it there because it provides a 9V voltage source that the PID uses to switch the relay on and off. I could replace it with a pull-up resistor, but I haven't gotten around to it yet.

I did want to mention that I do have a ground wired through the box, and connected to the metal shank of the heatstick. The other protection that is the most important part of the system is the 2-pole GFCI circuit breaker that I installed in my breaker panel. This is what will save me if a short happens, as it did already once (my heatstick was not sealed properly with enough J-B weld...had to re-seal it..no problems since.) GFCI breakers monitor current flow in each circuit (i.e. both phases of 120VAC going to my box/heatstick) and if there is ever a difference (meaning there is a short to ground somewhere in the circuit) of as little as 2-3mA between their currents, the breaker trips.

While the heatstick uses 240VAC, the way this is delivered is via 2 different phases of 120VAC that look like 240VAC to the heatstick. So, while you'll notice I have a warning sticker on the top of my relay saying 240VAC, it is actually only 120VAC going through the relay. The other phase of 120 is wired through the box directly to the heatsticks second terminal.

Below is a functional block diagram of the entire box, including the unused Controller Board.

Here is a picture of the top of the control box. Of course, I ordered a PID with Celcius readout, and I never did memorize that conversion formula....something like 9/5 times temp plus 32? or is that minus 32?

Here is the box with associated wiring/connections. to the right is the thermocouple. The short white 120V plug at the bottom powers the PID. The gray 220VAC plug brings power into the box, and the black 10-3 cable coming out the top left is wired into the heatstick.

As I did in my last post, my disclaimer here is that I am not a licensed electrician, and if you are not knowledgeable about electricity/electronics you should consult one.

If anyone wants more details, let me know.

This setup has been working great for me. I love the fact that I don't have to worry about running out of propane, and I can brew indoors in my basement shop in the winter, or during inclement weather.

I know that the efficiency of a heatstick tops propane burners, as all of the energy from the heatstick goes right into the water.

Thanks again to the entire brewing community for all of the ideas that I've borrowed from to end up with my system!

If you're gonna be serious about brewing, we recommend these essential books:

Originally, I did not consider a PID as adding a thermocouple into the mix was over-complicating things in my view. I settled on a design that was detailed in the Homebrewtalk forum and used a small circuit card to control a solid state relay which switched power to the heatstick.

The picture below shows the semi-rat's nest inside my box. One day I hope to clean it up a bit. My apologies for not having it all prettied up like many of the other projects I have seen detailed.

The first version of this box used the Control Board to turn on the relay every so often based on the setting of the potentiometer (round silver component on far side of box). By turning the knob on the outside of the box (connected to the potentiometer), I could control whether the heatstick was on for 1 second every 12 seconds, all the way up to 11.5 seconds of every 12 second interval. The relay switched one of the 2 phases of 120VAC to the heatstick, effectively turning it on and off.

This worked OK during mashing (although still not ideal), but to get my pot up to boil, I needed the heatstick on all the time.

To accomplish this I added the Bypass Switch (shown above) that bypasses the relay, and (when turned ON) keeps the heatstick on continuously. Once I got to a boil, I turned this off, and went back to the timer (technically a variable duty-cycle) approach circuit to control the heatstick.

Since the heatstick is so powerful (5500W), I could not keep a constant boil using the timer circuit. The instant the timer switched off the heatstick the boil would stop. So I decided to buy one of the PIDs so often seen in homebrew projects to see if that would improve the boil as well as the mash temperature control. Mine was around $20 on ebay and displays temperature in degrees C.

With the PID installed, I was able to control temperature quite nicely by dropping the thermocouple into my pot and setting the digital controller (PID) to the desired temperature.

I no longer need the Controller Board in the box, but have left it there because it provides a 9V voltage source that the PID uses to switch the relay on and off. I could replace it with a pull-up resistor, but I haven't gotten around to it yet.

I did want to mention that I do have a ground wired through the box, and connected to the metal shank of the heatstick. The other protection that is the most important part of the system is the 2-pole GFCI circuit breaker that I installed in my breaker panel. This is what will save me if a short happens, as it did already once (my heatstick was not sealed properly with enough J-B weld...had to re-seal it..no problems since.) GFCI breakers monitor current flow in each circuit (i.e. both phases of 120VAC going to my box/heatstick) and if there is ever a difference (meaning there is a short to ground somewhere in the circuit) of as little as 2-3mA between their currents, the breaker trips.

While the heatstick uses 240VAC, the way this is delivered is via 2 different phases of 120VAC that look like 240VAC to the heatstick. So, while you'll notice I have a warning sticker on the top of my relay saying 240VAC, it is actually only 120VAC going through the relay. The other phase of 120 is wired through the box directly to the heatsticks second terminal.

Below is a functional block diagram of the entire box, including the unused Controller Board.

Here is a picture of the top of the control box. Of course, I ordered a PID with Celcius readout, and I never did memorize that conversion formula....something like 9/5 times temp plus 32? or is that minus 32?

Here is the box with associated wiring/connections. to the right is the thermocouple. The short white 120V plug at the bottom powers the PID. The gray 220VAC plug brings power into the box, and the black 10-3 cable coming out the top left is wired into the heatstick.

As I did in my last post, my disclaimer here is that I am not a licensed electrician, and if you are not knowledgeable about electricity/electronics you should consult one.

If anyone wants more details, let me know.

This setup has been working great for me. I love the fact that I don't have to worry about running out of propane, and I can brew indoors in my basement shop in the winter, or during inclement weather.

I know that the efficiency of a heatstick tops propane burners, as all of the energy from the heatstick goes right into the water.

Thanks again to the entire brewing community for all of the ideas that I've borrowed from to end up with my system!

If you're gonna be serious about brewing, we recommend these essential books: